The Zoological & Botanical Gardens

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the southern slopes of Headingley Hill were still open fields. In 1837, four of these fields above Chapel Lane were bought for a new pleasure garden, and surrounded by a wall (much of which survives). The project (principally supported by Headingley residents) was both ambitious and controversial, and in 1840, Leeds Zoological & Botanical Gardens were opened, intended to rival similar gardens in London and elsewhere. But the Gardens were not successful, they closed in1848, re-opened under new management, as Leeds Royal Gardens. But these too failed, and closed in 1858. The land was finally put up for development, and beginning in 1868, a new road named after Lord Cardigan was laid through, and building plots on either hand were sold.

The rise and fall of the Gardens is described here by Janet Douglas.

Photographs by kind permission of National Portrait Gallery, Leeds Library and Information Service, University of Leeds, The Thoresby Society, Jerry Hardman Jones (JHJ), Helen Pickering, Richard Tyler (RT). Some photographs are subject to copyright and should not be reproduced without the owner's permission.

There is also information on the Gardens in Chapter 10 of Eveleigh Bradford, Headingey: This Pleasant Rural Village, Northern Heritage, 2008; see also, Eveleigh’s talk ‘The most beautiful Public Gardens in England’.

And click here for an audio walk round A Garden through Time that follows the footprint of the Old Gardens, prepared by Matthew Bellwood and produced by 365 Leeds Stories, with contributions by local residents.

For the Marshall family and Tommy Clapham, go to People in the Past. Also see the article on the proposed restoration of the Bear Pit.

JANET DOUGLAS

Leeds Zoological and Botanical Gardens

On 24th December 1836 a letter appeared in the Leeds Mercury proposing to establish a botanical gardens in Leeds, signed by Disney Thorpe, a physician at the Infirmary, he explained:

‘no one can have failed to have observed that whilst the wealth, importance and population of this town have gradually increased, the opportunities for public recreation have in ratio diminished’ Enclosures and the spread of buildings, ‘render it everyday more difficult for the labourer and artisan to breath in pure and uncontaminated atmosphere’.

Dr Thorpe’s proposal was to establish a society in the form of commercial company which would raise between £10,000 to £20,000 in £10 shares, and pay ‘a fair return’ (probably about 4%) on any investments made. The venture met with sufficient support for Edwin Eddison a Quaker solicitor and clerk to the Corporation to announce, again in a letter to the press, that a public meeting would be held at the Court House (which once stood at the bottom of Park Row) on 22nd May 1837 under the auspices of the mayor, to discuss the formation of the Leeds Botanical Gardens.

The background to this project was that all over the country, there was concern about how the working classes spent their leisure time. The breakdown of the old pre-industrial social order had liberated the workers who flocked to the new industrial towns, from the traditional controls of church and the squire. This lack of social control, in the eyes of the middle class, resulted in ‘depraved and immoral’ behaviour which was a threat to public order.

It was in this context that Parliament set up the 1833 Select Committee on Public Walks to inquire into the availability of green spaces in industrial towns and in the course of their investigation, they heard much evidence concerning the ‘low and debasing pleasures’ of the working class, their unruly behaviour and lack of personal cleanliness. John Marshall, the great flax spinning magnate who actually lived in Headingley, gave evidence to the Committee. Responding to a range of questions, he stated that the only open spaces in the town were the three moors at Woodhouse, Holbeck and Hunslet (for a population that was now 72,000), and he believed that the Corporation would be prepared to levy a rate to establish public walks, or alternatively wealthy individuals living in the town would be willing to subscribe to such a project. When asked if the working classes should pay an admission charge, his vehement answer was that charging would be ‘impractical’. The Select Committee recommended that walks should be established on the edge of all towns financed either by the rates or by voluntary subscription, a recommendation that was reiterated the following year by the Select Committee on Drunkenness.

Although Leeds Corporation did not take up the recommendation of public walks financed from the rates, as we have already seen there were sufficient concerned individuals amongst elite groups in Leeds for a private venture to be mounted. Already in Sheffield, subscribers to the Sheffield Botanical and Horticultural Society had established their own Gardens in 1833 (not open to the public) and similar gardens were springing up in places like Liverpool and Manchester and Birmingham. Spurred on by inter-city rivalries which were so important 19th century public affairs, the Leeds patricians must have felt that they couldn’t be left behind.

Besides offering pleasurable recreation, gardens also had the more serious purpose of affording opportunities for scientific self- education through the study of Botany and Horticulture. The scheme that emerged in Leeds appears to be something of a hybrid venture. The prospectus circulated amongst prospective shareholders explained that the purposes of the garden were to provide:

‘elevated pastimes for the operative classes and wean them from their grosser pursuits and offer an inducement to spend their hours of leisure in the pure breeze of country air … the objects of the Society besides affording the means to agreeable and useful recreation, is the promotion of the sciences of Zoology and Botany and their practical application to the various departments of Agriculture and Horticulture’.

The gardens were therefore not intended solely as a working class leisure facility, it was believed that they would attract the patronage of the middle classes particularly those who championed the idea of progress through the advancement of science. Such cross-class ambition echoed another common concern of the period: increasing social and residential segregation was damaging social cohesion and depriving the workers of models of ‘proper behaviour’, and therefore what was needed were arenas for social mixing that would have a civilising effect upon the working classes.

In the week following the May meeting at the Court House, £8000 was raised from the sales of shares which ranged from the purchase of single £10 shares to the two hundred shares purchased by John Marshall, and his son, Henry Marshall. The subscription list shows that all the wealthy families in Leeds whether Anglican or Dissenter, Whig or Tory, subscribed to the gardens, a rare instance of middle class harmony which as we shall see, was soon to be dissolved by a serious disagreement. The majority of the 1100 share owners were not grandees and many owned only a couple of shares. Formal authority in the company was vested in its annual general meeting of all shareholders and this body elected a committee of 21 (usually from amongst the grandees) that controlled the more detailed management of the gardens. However after the initial rush of enthusiasm, share purchases slowed down, but nevertheless an optimistic Committee went ahead and spent £5000 purchasing four fields from the former Bainbrigge estate just south of Headingley village. Interestingly two of the fields were owned by Dr Thorpe!

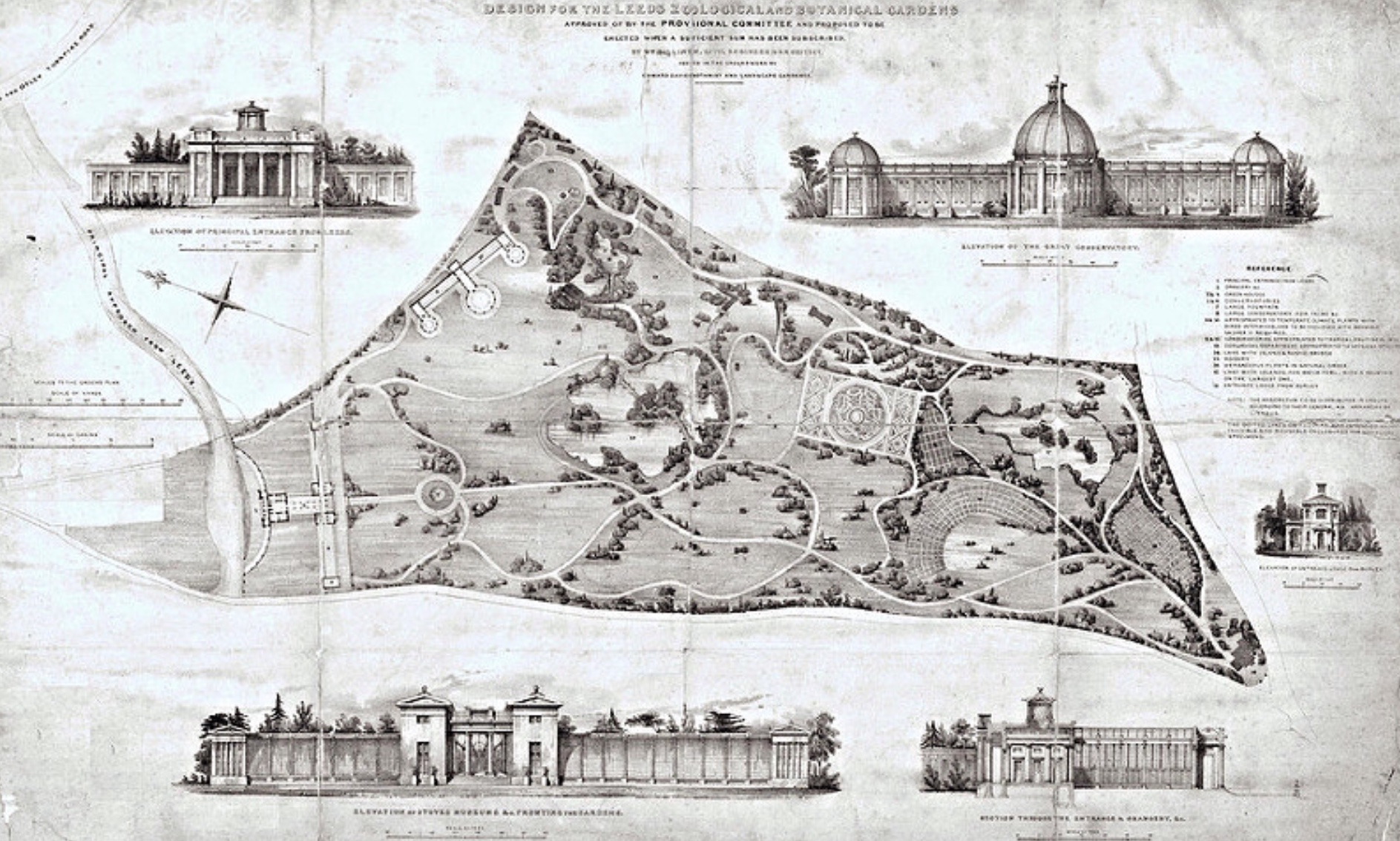

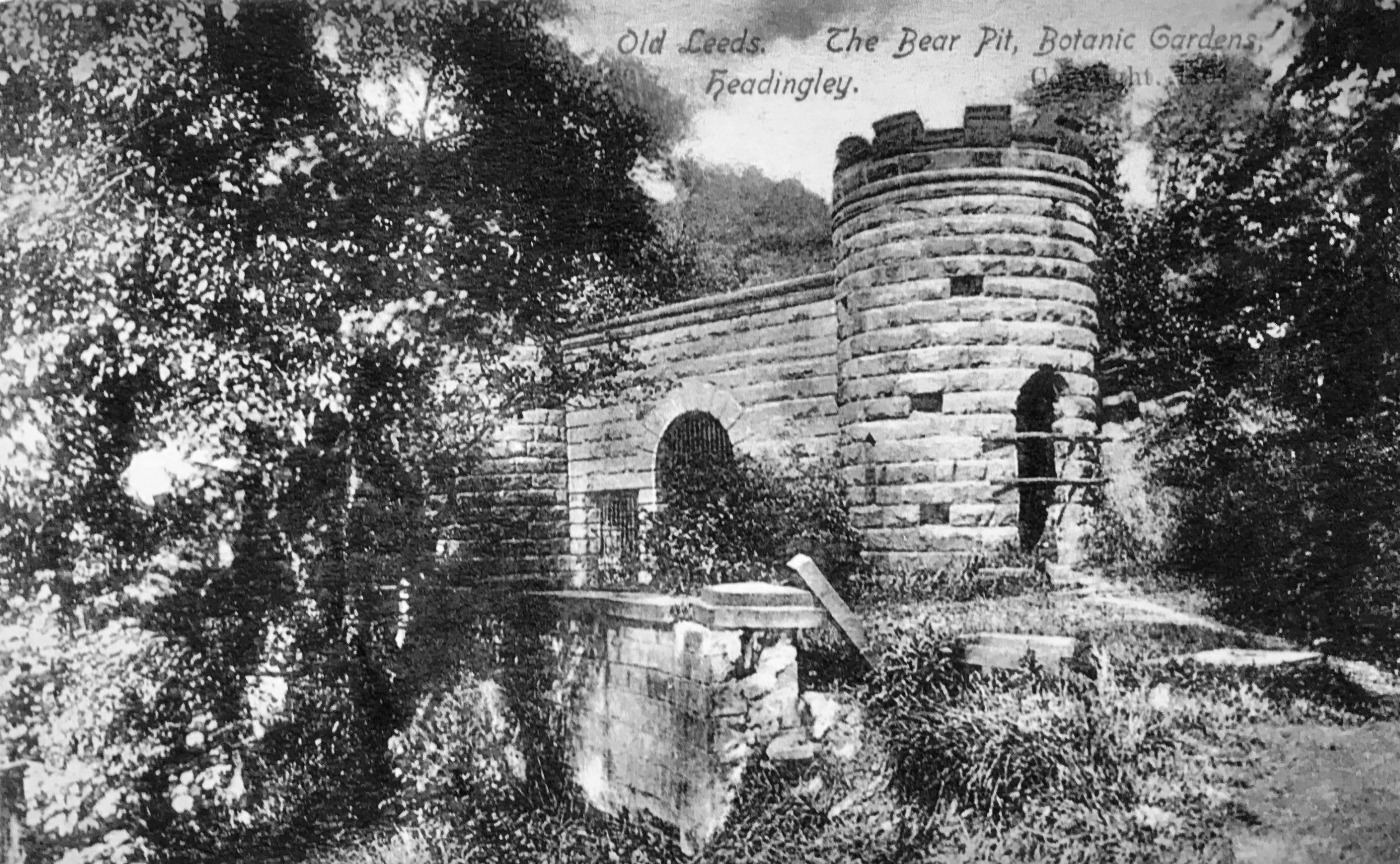

A competition organised for the design of the gardens, was won by a Wakefield architect, William Billinton assisted by Edward Davies, a botanist and landscape gardener. Their plan was heavily influenced by the ideas of J.C. Loudon, the designer of Regents Park: a mixture of formality and the picturesque: there were to be formal classical entrance lodges and conservatories, with winding walks, fountains and grottoes, small lakes with rustic bridges, all surrounded by a high stone wall. But this plan proved to be over-ambitious and was never fully realised for financial reasons. Only a little over £11,000 was raised from the sale of shares and throughout their existence the gardens laboured under a debt of £6,000. A plan of the gardens shown on Fowler’s 1844 Map of Leeds shows none of the grand classical structures outlined on the Billinton plan, there were however, two lakes, plenty of winding paths, trees and flower beds and a feature not included initially, a bear pit.

The gardens were formally open on 9th July 1840. The ceremony was attended by two thousand people of ‘all ranks’, flags flew from the two entrances, bands played, there were two refreshment tents but the promised ascent of a hot air balloon, a favourite spectacle of the period, failed to happen due to a fault in the gas supply. It also rained for part of the day. The Leeds Intelligencer, the Tory paper whilst generally supportive, was critical of the lack of water in the fountain and was shocked because the day’s celebrations were rounded off by three live birds being placed in a cage of hawks who promptly tore them apart. No doubt intended as a natural history demonstration of the behaviour of birds of prey, in an age of sensibility, it was deemed by the Intelligencer to be highly offensive. This spectacle was not mentioned by the Liberal Leeds Mercury. Their report informed readers that that the gardens were: Surrounded by a high wall within which on the west, south and east, is a plantation of trees in proper botanical arrangement, and on the north are fruit trees trained against a wall. Beautiful slopes of grass, tasteful parterres and shrubberies, with winding walks, two very handsome ponds with islands and a beautiful fountain. Near the entrance to the grounds from Headingley is a conservatory containing a beautiful collection of geraniums and a variety of exotic plants and flowers. The Zoological department as yet confined to a fine pair of swans and some other fowl, monkeys and tortoises.

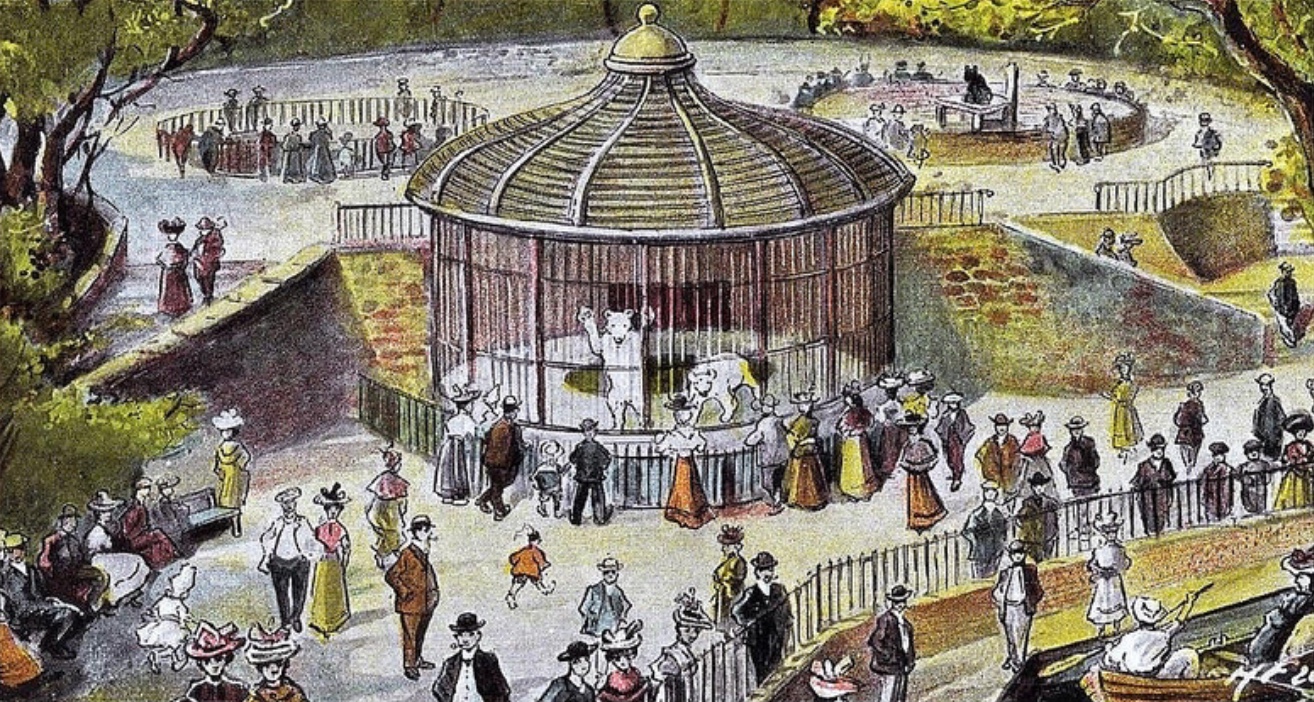

‘The Zoological Department’ was always fairly limited. In 1838 the committee had contacted George Wombwell, the famous menagerie owner to ask how many animals might be purchased for £1000. He replied that elephants were out of the question but a pair of lions might be purchased but he wisely reminded the Committee that they would need keepers and feeding! It wasn’t until 1843 that the Gardens acquired their first and only large animal exhibit, a bear, and this purchase was an effort to boost visitor numbers.

Admission prices were 6d for adults, 3d for children under 13 and 3d for servants accompanying children, reasonable charges for a middle class family but with workers’ wages rarely exceeding a pound a week and many receiving less than 10 shillings, clearly a visit to the Gardens for them, was a major financial outlay. The opening of the gardens also coincided with a serious ‘stop in trade’ that lasted throughout the 1840s. The matter of accessibility to the Gardens might also have deterred visitors. The Gardens were close to the road which ran between Leeds and Headingley, and there was a horse-drawn omnibus service but this added to the expense of a visit. Working class people were certainly used to walking what we would regard as fairly long distances. Probably the major reason for the lack of visitors was the decision taken by the shareholders not to open the gardens on Sundays, the only day when employees were not at work.

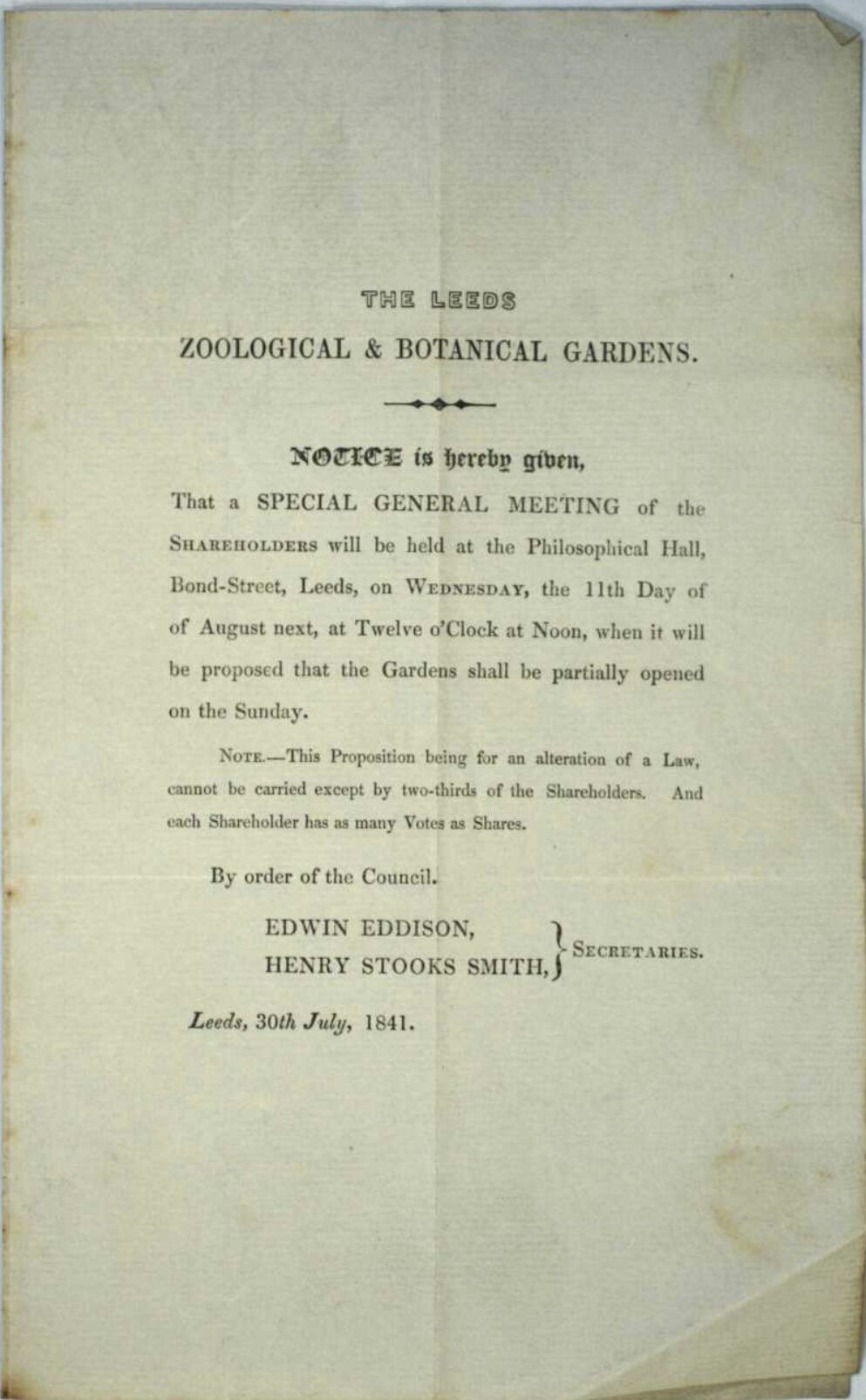

For many moral reformers, the observance of the Sabbath was a critical issue and one that united Anglican Evangelicals with Dissenting groups like the Methodists and Congregationalists. Sermons against Sunday opening had been preached in a number of the town’s churches and chapels. As the gardens failed to attract visitors and no dividends were ever paid, more radical, secular-minded shareholders raised the question of Sunday opening. Throughout 1841, a sectarian debate raged in the local newspapers and matters came to a head with the calling of a special general meeting in August to discuss the resolution that the gardens should be open on Sundays after 4pm. Under the contentious headline, ‘Public Desecration of the Sabbath’, the Mercury reported the acrimonious meeting attended by over 400 shareholders (out of a total of 1,140) at the Philosophical Hall. Hamar Stansfeld, a Unitarian and a member of the Society’s Committee referred to how an attempt a few months previously to recruit more shareholders had failed because the gardens were not open on Sundays, and that existing shareholders now had to face up to the fact that Sunday opening was the only alternative to the closure of the gardens which would be ‘a disgrace to the town’. John Atkinson, the Anglican and Tory solicitor disagreed. An opponent of Sunday opening, he described the conflict as ‘a clash between principle and pence’. He expressed his fears that ‘large numbers of the working classes spent their Sundays in public houses and if the gardens were open, they would come there instead but they would drink in the neighbourhood instead of the neighbourhood of Marsh Lane’. Other local residents were also worried about the consequences of Sunday opening on the peace of the neighbourhood. But Thomas Nunneley, a surgeon at the Infirmary, argued the working classes only desecrated the Sabbath because they were presented with few alternatives, whilst George Goodman, a Baptist and first mayor of the reformed corporation, argued that Sabbath observance was a matter of individual conscience. ‘A man visiting the gardens and observing the beautiful things around him would be induced to look through Nature to Nature’s God’ and would be struck with the existence of a creative power above and with his goodness to all His creatures’. Frederick Baines, the editor of the Mercury voiced his concern that servants and hackney cab drivers would be forced to work on the Sabbath. When the vote was taken, 388 supported Sunday opening whilst 34 opposed. John Atkinson immediately announced that he would sell his shares and expected others would do likewise. In order to appease their opponents, the Committee decided that admission tickets would not actually be sold on Sundays but instead should be purchased on Saturday from a shop on Briggate.

At one level this debate was about religious differences – Unitarians, Baptists, Quakers and some Anglicans argued in favour of Sunday opening, but also underlying the religious divide, were different attitudes to the working class and how best to modify their behaviour. Some speakers revealed more optimistic and paternalist attitudes, whereas others were clearly extremely distrustful of the lower classes and preferred the use of control rather than persuasion. Edward Baines, for example, in a later letter to the family newspaper, presented an alarmist account of what would be the results of Sunday opening on the genteel suburb of Headingley:

You bring together a crowd of people, of both sexes and ages, without any means of rendering the company select. I need not say that the vilest characters as well as the most frivolous, worldly and worthless are more abroad on the Sabbath than on any other day. Here you offer them a public attraction which concentrates them in one place. You gather them out of the streets, out of the highways and hedges, and bring them to a focus. If they shall have bought tickets you cannot refuse them admission. I do not know that you can exclude abandoned females …See the kind of company into which our youth are likely to be thrown on the afternoon of the Sabbath as a means of improving their morals and cultivating their piety.

Meanwhile Samuel Smiles writing in his paper, the radical Leeds Times, believed that the whole debate was ‘proof of the entire lack of sympathy between the governing caste and the labouring community’ and that ‘Sabbath freedom was part of the great question of civil and religious liberty’. A month later, the Leeds Times published a letter under the by-line, Sabbath Breaking by Whom? , gleefully reporting that Edward Baines himself had been spotted in his carriage returning to Leeds along North St on a Sunday afternoon, sarcastically the Times correspondent suggested that he might have been ‘comforting the halt and the lame of Harrogate’, rather than merely enjoying a afternoon ride in the country!

Although some of the promoters of the gardens never envisaged them as a recreational facility purely for the working classes, in my research I have not come across any accounts of middle class visitors to the gardens, perhaps the lack of social exclusivity was the reason. James Bedford who eventually built a villa in Cardigan Road, recalled in 1935, visiting the gardens as a boy and feeding buns to the bear; William Williams Brown, the Chapel Allerton banker and shareholder, in his meticulously-kept personal financial record books makes no mention of visiting the gardens himself though he did pay his housekeeper 5s to take his servants there as a treat. In his diary entry for 6th June 1843, the Pudsey manufacturer, Reuben Gaunt records: Went to the Zoological Gardens, Leeds, to a temperance festival, partook a good tea and after hearing the Trial of John Barleycorn, played various rural sports.

Galas, festivals and shows appear to have been the financial mainstay of the gardens. A year before Reuben Gaunt’s visit, a procession one and half miles long, had walked from Leeds to a temperance gala held in the gardens. The Leeds Horticultural and Floral Society founded in 1836, had their annual shows there, whilst later in the 1840s, the Leeds Archers Society established in 1847, held a Grand County Archery Fete for two years running. Special excursion trains were organised from across Yorkshire and besides various archery competitions with cash prizes, there were two bands, a cold collation with wine and a concert by a group of glee singers. There were also special charity events such as the one held in April 1841 in aid of Funds for the Establishment of Rocket Stations on the Coast of Yorkshire for the Preservation of Life. This not surprisingly involved a display of the said rockets and admission charges were 1s for adults and 6d for children.

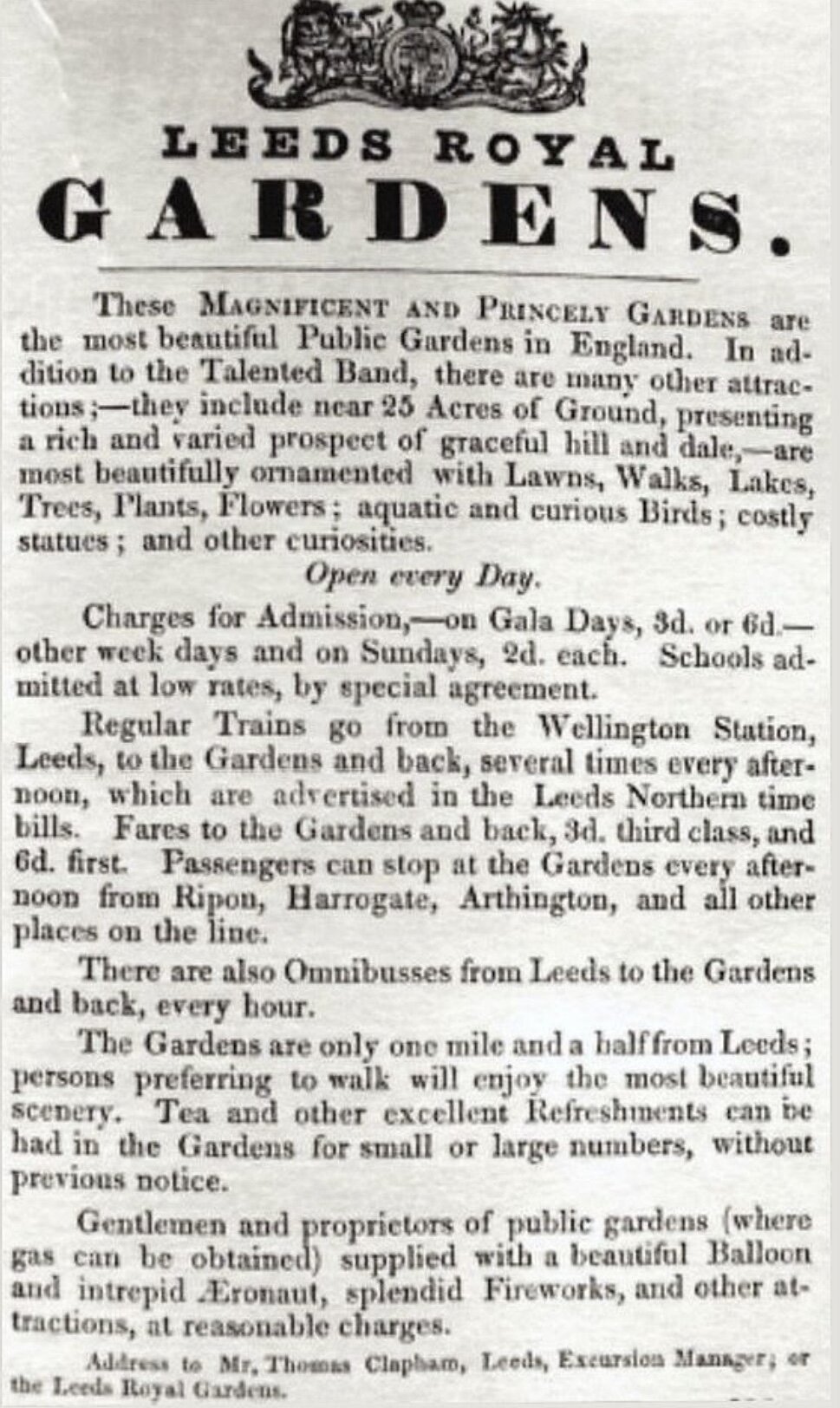

Teetering on the edge of financial insolvency for many years, the gardens first closed in December 1848 and were sold at public auction to James Smith, a banker for £6000. Smith’s intention was to develop the site for housing but this fate was deferred for another ten years or so years when Smith sold the gardens to Henry Marshall who in turn leased them to Thomas Clapham. To ameliorate problems of access Marshall persuaded the proprietors of the Leeds-Thirsk Railway to allow a train halt at the southern end of the gardens; admission prices were reduced and the gardens were open on Sunday from 1pm with an entry charge of 2d. The name of the gardens changed to the Leeds Royal Gardens and rather than an emphasis on self-improvement and education, there was a shift to amusement and spectacle.

But even Clapham’s showmanship élan could not make a financial success of the gardens and they finally closed in 1858. Clapham went on to open the new Royal Park Gardens opposite Woodhouse Moor with a more down-market focus on physical activities including cricket, a gymnasium and what was described as ‘ the largest dancing platform in the world’. Marshall reverted to the earlier idea of developing the area for housing.

What remains of the gardens today? Best-known, of course, is the bear pit, but Spring Road was probably laid out to provide access to the Gardens from Headingley Lane. Much of the original stone wall that once surrounded the Gardens can still be seen particularly along Chapel Lane. Remnants of the entrance at the north end are still visible at the junction of what is now Cardigan Road and Chapel Lane. The indentation of one of the lakes lies in front of Valley Court, and the base of a fountain can be found in nearby Cardigan House. Both houses were built in what was described at the time as the Old Gardens Estate laid out for Henry Marshall [see Appendix]. The glorious trees which line both sides of Cardigan Road are another legacy, and more serious detective work by landscape historians might well uncover other hidden features of the ill-conceived and doomed Leeds Zoological and Botanical Gardens.

This text is based on a talk given by Janet Douglas for the Left Bank Leeds’ ‘Talking History’ series on 15 February 2018. The series was made possible with the kind support of the Heritage Lottery Fund. To find out more about future talks and events go to www.leftbankleeds.org.uk